Smalltalk – The Syntax Issue

I recently watched a YouTube video by “Uncle Bob” entitled “The Last Programming Language,” in which the speaker predicts what he believes will be the features of the last, best programming language. After discussing several currently popular languages (C++, Java, JavaScript, PHP, Python, etc.), he admits that all these languages are essentially rehashings of the control and data management statements of older languages, such as Fortran, COBOL, and PL/I. He sees the same kinds of statements for assignment, alternation, looping, data management, and functions in all of them, each with its own syntactic peculiarities.

For example, consider the JavaScript statements,

for (i=1 ; i<=9 ; i=i+2) {do this}

if (age < 16) {then do this} else {do this}

These statements must be specified exactly as required by the JavaScript compiler, using the reserved keywords “for” and “if” and the exact “(){};” punctuation. Instead, Uncle Bob said, it would be better to do away with all that syntactic sugar and have a simple syntax in which all statements can be expressed. This is an idea he could well have taken from APL, or Smalltalk.

The equivalent Smalltalk statements are:

1 to: 9 by: 2 do: [aBlock]

age < 16 then: [aBlock] else: [aBlock]

The message “to:by:do:” can be sent to any class of numeric object that implements looping, and the message “then:else:” can be sent to any Boolian object, such as True, False, or the result of evaluating a Boolian expression, such as “age < 16”. These are not special statements supported by the Smalltalk compiler and the only keywords Smalltalk recognizes are self, super, and nil.

There are only three kinds of messages supported by the Smalltalk interpreter: unary (as in “5 factorial”), binary (as in “3 + 5”), and keyword (as in “to:by:do:” or “then:else:”). The object returned by a method can then be the receiver of a subsequent message enabling efficient coding without intermediate variables.

Smalltalk programmers are free to invent whatever control statements they want—just add new methods to classes to handle the new messages. Of course, useful Smalltalk classes are shipped with a variety of useful methods for working with numbers, strings, collections, etc. The collection methods are particularly expressive and powerful. Beyond that, you can invent whatever classes of objects you need and the messages that can be sent to them.

One of the major criticisms of Smalltalk is that its syntax is too different from the C-like statements that most programmers are used to. It is different, but in truth, it is easily learned if one can get past the inertia needed to learn something new.

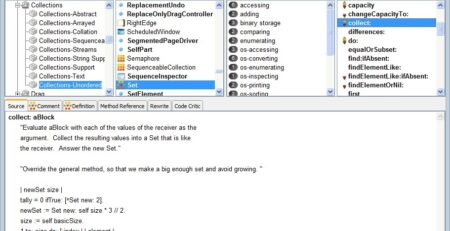

Consider the snippet of Smalltalk code in the figure above this post. Assume that “self” represents a customer trying to check out of an online vendor. Without difficulty, this carefully written code can be read as if it had been written in English.

Having to work within the Smalltalk IDE is a higher hurdle for programmers used to using text editors, but it, too, quickly becomes second nature and provides a variety of powerful coding tools.

Questions:

How many languages do you need to know to do your job? Do the syntactic differences annoy or confuse you?

Leave a Reply